- Home

- Clyde Burleson

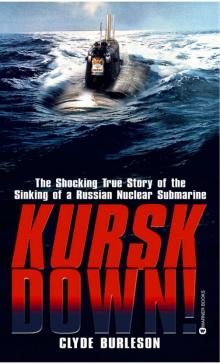

Kursk Down Page 8

Kursk Down Read online

Page 8

A radio link to Norway’s Marjata electronics intelligence ship, which by some accounts had been leased to the CIA, helped clarify the movement patterns. Many of the vessels seemed to be engaged in a search exercise.

13 August 2000—1615 Hours—On Board the Rudnitsky

The immensely powerful DSRV submersible bore the service number AS-34. She was classified as a Briz, which designated her size and capabilities. A little over 30 feet in length and 12 feet wide, she packed a lot of technology into a small space. Her battery-powered motors could drive her slightly more than 3 knots. At a lower speed of 2.3 knots, maximum range was 21 miles. She was also able to lift and carry other vessels weighing up to 60 tons.

The AS-34 could dive to a maximum depth of just over 3,000 feet and remain submerged between two and three hours. Those capabilities were more than enough for this mission.

Being lowered into the water from the deck of the Rudnitsky was a trying experience. As noted previously, the mother ship had originally been designed as a lumber carrier. Extensive modifications had been made to allow it to perform its present mission. And while the conversion was adequate, the seamen had to exercise great caution to prevent damage to the DSRVs.

Once safely floating in the sea, the AS-34 crew hurried to submerge. The shape of their craft made it susceptible to wave motion while surfaced. Pitching and rolling were acute. Working quickly, they established a radio link with the Rudnitsky, performed the balance of their prediving checks, and were ready.

Motors whirring, the minisub gently slid beneath the waves. As the boat descended, light from the sky above began to fade from clear to a gentle violet to deep blue. At a depth of 200 feet, there was total darkness. Even with the running lamps and main spotlight, vision was limited because of stirred silt. The crew knew that nearer the bottom it would be even worse.

Several electric heaters kept the inside of the rescue sub reasonably warm. As she went deeper, it would grow colder.

In reporting conditions to the surface, comments were made about the low visibility. All were thankful they had an electronics trick that could lead them to the Kursk. Otherwise, they might spend days hunting blind.

Flying the small submersible required constant attention because of variable undersea currents. The ride, though, was smooth, and changes in direction or depth were as easy to make as in a light plane.

The pilot was searching for a place with negligible current at a depth of about 200 feet. When he found it, he aligned the boat by compass so that it was pointing in the same direction as the Rudnitsky, far above them on the surface.

Easing back slowly on the throttle and adjusting their buoyancy brought the DSRV to a complete stop. To execute the plan, the minisub would lie quiet. Experts on board the Rudnitsky would then send out a strong sonic probe or ping and a radio signal. There was an automatic acoustic station on board the Kursk. If the probe hit it right, there would be a response ping from the sub. The crew would then record and home on that signal.

With the motors stilled, it was quiet inside AS-34—so quiet in the deep it was possible for the men to hear their own heartbeats. Then the Rudnitsky’s probe, ringing like the metallic ting of a spoon hitting a crystal goblet, was loud in the minisub. At 1620 hours, there was a solid response.

Working frantically to intercept the contacts being traded between the Kursk and Rudnitsky, AS-34 powered cautiously forward, then back, then to one side. All the while, the electronics specialist on board tried to align his equipment with the generated signals. It took over an hour. At 1748, they had their lock. It was tight enough to give them a proper fix.

Easing ahead through the blackness was like driving a car on a strange road at night in a dense fog. Their lights were absorbed by the silted water. At times, visibility was less than a yard.

Speed was now measured in feet instead of miles per hour. Then the sonar indicated a monstrous shape dead ahead.

Disaster struck at about 1830 hours. With a horrendous steel-slamming clang, the minisub gave a jolting lurch. They had hit the Kursk. Their impact point was, as best they could tell, on one of the sub’s large steering wings.

Fear of serious damage caused a hasty safety assessment. Fortunately, only a few leaks were found. Their hull remained intact.

In spite of calling the situation an emergency, they made another pass. This time they lucked into a clearer view. With this visual confirmation, they contacted their mother ship. A satellite fix was taken on their location and the rescue fleet had the Kursk’s precise coordinates. After recording the depth, water temperature, and the angle between the sub and the sea floor, they were satisfied they’d done all they could on this first trip and surfaced.

After a few minutes of jockeying for position, the AS34 submersible was hooked onto a crane and lifted from the water back to the Rudnitsky’s decks.

According to a statement attributed to Alexander Teslenko, the exact seabed location of the Kursk was established in 6 hours and 27 minutes after the search party had been dispatched—a commendable feat.

While the crew quickly made their reports, a repair team swung into action. AS-34 would be needed again in this rescue mission. As work proceeded, two other operations were given top priority.

The Rudnitsky once again changed locations. The ship now assumed a position over the site of the wreck. The second DSRV, registered as AS-32, was readied for use.

Other ships had been arriving, including the rescue team’s tugboat and the Altay, which managed twice to deploy a diving bell. Shaped like an early space capsule, a bell acts as a kind of undersea elevator. Divers breathing normal air can remain at depths of more than 300 feet only a few minutes due to the pressure on their bodies. They ride in the bell, which is kept at the standard one atmosphere and lowered quickly. Once on the bottom, they venture out for the allotted maximum safe period. Then they reenter the bell and are lifted back to the surface.

Since the bell on the Altay was used, the Russians clearly had divers on or near the Kursk. Contrary to published reports insisting the high command of the Northern Fleet did not yet know the actual condition of the Kursk, the presence of divers, along with other evidence, indicates the opposite. Divers were sent to survey the damage and, by hammering on the hull, attempt to determine if there were any survivors.

Sea and weather conditions remained good and the early success boosted morale—as did a rumor. Some were saying there had been sounds from the Kursk. The knocking was like someone hammering in Morse code on the inside hull. The tapping was weak and reportedly read “SOS. Water.” Recordings were made for better analysis. No one was sure if these sounds were actually signals. The possibility brought hope.

Aboard the Peter the Great

A very thoughtful Admiral Popov, who had assumed overall command of the rescue operation, had returned to his flagship, the Peter the Great. The decision had been made to focus on recovery of personnel aboard the lost submarine. It is possible and even probable that certain individuals already knew any rescue activity was a lost cause. Even if they did, sending aid was the best option. When word of the disaster reached the news media, it would be imperative to have more than the appearance of an effort to save lives.

Press notification merited top attention. The first question that would be asked by the news media was obvious. What had happened? The initial answer to that query was established. The Kursk was lost because of a collision with a foreign vessel—probably a submarine. When the time came to inform the press, the collision response had to be introduced by high-ranking individuals. This would serve to increase the veracity of that position. No less a personage than Deputy Prime Minister Ilya Klebanov, who was soon to be named chief of the government commission appointed to investigate the disaster, was one of the earliest, if not the first, proponents of the collision theory in the media.

The “foreign sub” story had to be uppermost in everyone’s mind during this operation, because any hard evidence that could support the collision theor

y would make that position more believable. So every opportunity to search for “proof” had to be taken.

A well-conceived political damage-control program must also offer other reasonable explanations for the disaster. These help create a diversity of public opinion, thus confusing the issue. Alternate causes also provide failsafe positions in case the main theory does not catch on or cannot be proven. There was only one prime requirement for all the officially recognized possibilities. None could cast blame on the Navy or Russian government.

For certain, the press was going to demand answers. And if enough facts were not forthcoming, reporters would dig until some were found—or worse, use flights of fancy to explain the cause of the catastrophe.

Another burning problem came from the ever-present danger of leakage from a damaged nuclear reactor. While the disaster was bad enough, the situation would grow far worse if there was nuclear contamination. Release of radiation was of immediate importance because the Barents Sea was one of the world’s most productive fishing areas.

The Navy would be in a much stronger position if positive assurances of proper reactor shutdown could be given as part of the initial release. This produced an urgent need to collect samples of seawater and metal from the Kursk’s hull. These specimens could then be analyzed to determine if any danger existed. So sample gathering was an important part of the rescue effort.

In the early evening hours of Sunday, August 13, as activity at the Kursk site was building, Admiral Popov appeared on Russian national TV. From the deck of the Peter the Great, he declared that the Northern Fleet’s sea war games had been a resounding success. No mention was made of the Kursk.

Popov’s televised comments of that night would be remembered later and cause a major backlash. The official explanation for this seemingly devious act was that Popov’s remarks had been recorded earlier, before the Kursk disaster, and played on the Sunday show. That story is most likely true. No one, however, canceled the use of this prerecorded tape, which plainly shows a tendency to manipulate the news. And inadvertently or on purpose, that is precisely what was to happen.

2240 Hours—On Board the Rudnitsky

AS-32, the second DSRV, was successfully deployed over the side. Her mission was to get close-up television pictures of the wreck and especially the escape hatch to the ninth compartment.

During the next two and a half hours, the crew, hampered by poor visibility, made several descents. Proceeding cautiously, to minimize damage to their boat if they collided with the lost sub, they searched quadrant after quadrant. In spite of known precise coordinates, AS-32, for some unexplained reason, failed to make visual contact with its target.

Pressure to hurry the rescue effort was growing by the hour. So the now-repaired AS-34 submersible was rushed back into action.

The crew once again managed to locate the downed submarine, but was forced to resurface because of drained batteries. This setback brought about a costly, expedient decision.

In normal conditions, a complete recharge of DSRV onboard batteries takes some 13 to 14 hours. This period can be shortened, but doing so seriously depletes the useful life of the battery packs. Since these are expensive to replace, deciding to do a quick hotshot recharge demonstrates the urgency everyone was feeling.

Back in the water less than 60 minutes later, the crew went directly to the sunken vessel. AS-34 cautiously maneuvered to the stern escape hatch and made its first attempt to dock. Their goal was to mate with the hatch, open it from inside the DSRV, and thereby establish a dry escape route for trapped personnel.

The crew worked without break for almost three hours, using up much of their breathable air. They were unable to mount a rescue. A combination of poor visibility, undersea currents, the angle at which the Kursk rested on the bottom, and damage to the escape hatch docking flange, were all said to have played a role in the failure.

Since the Kursk was not lying horizontally, it was decided a later model DSRV, one of the two Bester (AS-36) units, would be better suited for the docking job. That model was designed to mate with a surface at an angle up to 45 degrees and could remain submerged a full four hours. An emergency call was put through ordering the deep submersible to the rescue site.

14 August 2000—1015 Hours

A large number of people were becoming involved in the rescue activity—which made keeping the loss a secret from the media progressively more difficult. The telephone censorship placed on Vidyaevo and some of the other villages where Northern Fleet personnel lived was also attracting media curiosity. Fearful of a leak, officials believed the best policy was to control information by making a preliminary press release. It was decided that the initial announcement did not have to reveal the actual nature of the situation. That could wait until the question of radiation leakage was resolved—and, it was hoped, after some evidence was found to back up the collision story.

Two days after the disaster, on Monday, August 14, at 1045 hours, the Navy Press Center issued the first public statement: “. . . there were malfunctions on the submarine, therefore she was compelled to lay on a seabed in region of Northern Fleet exercises in Barents Sea.”

While that account was not, on a word for word basis, a direct lie, it certainly did not reveal the seriousness of the accident. The first release also noted that the incident had occurred on Sunday, August 13, rather than Saturday, August 12.

Further information, this time a bit less truthful, indicated communications with the submarine were said to be working.

Shortly after noon, Vice Admiral Einar Skorgen, Commander North Norway (COMNON), used the red telephone in his office at COMNON headquarters located at Reitan. The facility was built deep inside a nuclear bombproof complex excavated from an Arctic mountain near the Norwegian town of Bodoe. Skorgen activated the direct line to Admiral Popov. This new straightthrough link had been established in April 1999 to further relations between the neighboring nations. It had never before been used. Acting under orders from the Norwegian Ministry of Defense, Admiral Skorgen, through an interpreter, requested details on the Kursk situation. He also offered direct assistance as well as a willingness to coordinate aid from NATO.

The Russian response was gracious and clear. Thanks, but no thanks. The matter was under control. No help was required.

At this point, that answer most probably summed up an honest attitude. The Northern Fleet had ample resources on-site and more assistance on the way. If the Navy high command knew the actual condition of the Kursk, such experienced men of flag and even lower rank would be able to perform their own damage assessment. Loss of a large percentage of the crew would be a foregone conclusion. The need for even more help would be hard to justify.

Besides, bringing in the Norwegians, or any foreigners at this junction, would have served as the detonator for a news media explosion. Worse, it would be an admission of Russian inability to care for her own men. And almost as bad, asking for help was like passing out an open invitation for any interested party to come and examine the most advanced submarine in their Navy.

1400 Hours—Rescue Site

NTV, the Russian independent television network, broke into its regular programming with a special bulletin. The Kursk was down. The submarine’s bow was damaged and flooded. All power generation on board the boat had been cut.

Armed with the Navy Press Office release, reporters had gone to work. At least one, and most likely more people with knowledge of the disaster, talked. Since few knew the extent of damage, there was a good probability that the someone who spoke was a ranking officer.

Two hours after the NTV report, the Navy denied any flooding and again placed the time of the incident on Sunday.

Apparently pressure from the news media developed rapidly. Two hours after the second Navy statement, Admiral Vladimir Kuroyedov, chief of the Russian Navy, admitted the Kursk was seriously damaged.

At the site, divers obtained water samples to check for radiation. Thus far, no contamination was detected. That

was the only bright spot, because the deep-sea TV camera modules, which carry their own light sources, provided pictures that indicated vastly more damage to the submarine’s front sections than had been anticipated. The Navy made no mention of this distressing fact.

By this time, and because of other Navy press confusion, obfuscation, and falsehoods, their Public Information Office credibility had been damaged. As the evening progressed, the foreign-sub ramming theory was offered as actual fact. There was also talk of an explosion on board. Denials and counterdenials abounded. Offers of help from foreign governments poured in.

Britain agreed to loan its LR-5 DSRV. This rescue vehicle had been modified when it was used to assist a Polish sub. Its escape hatch matched the Polish model, which was much like the Russian design.

The U.S., NATO, and Norway were all quick to volunteer aid. These offers produced another quandary for the Russian group orchestrating how the disaster could best be handled in terms of protecting careers, Navy image, and honor.

To accept help could well be construed as an admission that the Navy was incapable of doing the job. It would also sting national pride.

To refuse assistance might lay officials open to later charges of callous disregard for human life—especially if it was discovered that crewmen on the downed boat lived for days and the rescue work proceeded too slowly to save them.

To further complicate a messy situation, there was the question of equipment compatibility. With the exception of the modified British submersible, fittings of other nations would be incompatible with Russian gear. Therefore time had to be spent determining what outside aid might be useful and how best to employ those resources. Starting such discussions would immediately demonstrate a willingness to accept help, even though that assistance might not, after serious consideration, be beneficial.

The place to review possible help was NATO. Most of the nations offering aid were members and, after all, this was a military, not a civilian matter. Better still, confidential talks could be held at NATO headquarters in Belgium. That would minimize leaks to the Russian press.

Kursk Down

Kursk Down